Journal of Education and Learning; Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

ISSN 1927-5250 E-ISSN 1927-5269

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education

82

Creating Core Competencies and Workload-Based Key Outcome

Indicators of University Lecturers’ Performance Assessment:

Functional Analysis

Chatchawan Nongna

1

, Putcharee Junpeng

1

, Jongrak Hong-ngam

2

, Chalunda Podjana

1

& Keow Ngang Tang

3

1

Faculty of Education, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand

2

Faculty of Economics, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand

3

Institute for Research and Development in Teaching Profession for ASEAN, Khon Kaen University, Khon

Kaen, Thailand

Correspondence: Putcharee Junpeng, Faculty of Education, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand.

Received: August 22, 2021 Accepted: September 26, 2021 Online Published: October 24, 2021

doi:10.5539/jel.v10n6p82 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v10n6p82

Abstract

This research aims to create and validate the quality of performance assessment using functional analysis. The

researchers employed a design-based research method to create core competencies and their workload-based key

outcome indicators as a preliminary study encompassing two phases, before formulating a standards-setting

appraisal model to assess university lecturers in a public university, Thailand. The researchers began with

documentary research to identify core competencies of university lecturers from three clusters of educational

programs, namely science and technology, health science, and humanities and social sciences. An innovative

prototype of university lecturers’ core competencies was developed based on the obtained results from the first

phase. A total of five experts and 17 users participated to validate the quality of the innovative prototype. The

preliminary results reveal that there are four core competencies of university lecturers, namely teaching, research,

academic service, and preserving arts and culture. Moreover, there are 13 workload-based key outcome

indicators and 27 elements that resulted from the four core competencies related to the specific research

university in the Thai context. Moreover, the quantitative results of the content validity index from the rating

scales of the five experts indicate that the conformity index is 0.78 or higher. However, the qualitative interview

results regarding the 17 users from four focus groups imply that there is a gap regarding the accuracy of current

performance appraisal between lecturers’ core competencies and their actual workload. Therefore, the dean

should make the necessary adjustments based on the context.

Keywords: core competencies, functional analysis, performance assessment, workload-based key outcome

indicators

1. Introduction

The role of the university lecturer has a great impact on knowledge and cognitive development for society and

the nation (Blašková, Blaško, & Kucharþíková, 2014). Therefore, it is a highly demanding job that requires core

competencies and continual enhancement of professional knowledge and social competencies. This enables

university lecturers to conduct scientific research and transfer the scientific results to students for their future

development (Blašková, Blaško, Jankalová, & Jankal, 2014). University lecturers’ work performance can not

only have a significant impact on higher education implementation but also support the dynamic and

effectiveness of the education process (Akbar Ali & Si, 2015). The usefulness of performance assessment, in

general, can be categorized as the main contributor to the quest for reward and publishment, as a standard to

authorize the assessment, provide feedback to the university to serve as individual career development,

determine the purpose of the training program, and support the detection of organizational problems (Akbar Ali

& Si, 2015).

Key outcome indicators should be the following: specific, measurable, achievable and attributable, relevant and

realistic, and time-bound, as emphasized by past researchers (Allen, Fenemor, & Wood, 2012; Hocking,

Jacobson, & Carter, 2008; Leagnavar, Bours, & McGinn, 2015). This is because good indicators need to be

easily understood and eloquent to those who seek to use the information they provide. Therefore, Leagnavar et al.

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

83

define the specific characteristic of the key outcome indicators as capturing the essence of the desired result,

specifically related to the achievement of university lecturers’ performance assessment. Furthermore, the key

outcome indicators must be measurable, considering the repeatability of assessment, the precision required for

measurement, and the resources needed for measurement (Allen et al., 2012). Next, the achievable and

attributable characteristics refer to the performance assessment system to identify what changes are anticipated

as a result of the involvement and whether the results are realistic. In other words, attribution requires that

changes in the targeted developmental issue can be linked to the involvement (Hocking et al., 2008). The key

outcome indicators must be relevant and realistic to establish levels of performance that are likely to be achieved

practically and, thus, reflect the expectations of stakeholders (Allen et al., 2012). Finally, the time-bound

characteristic refers to the progress of work performance to be traced cost-effectively at the desired occurrence

for a set period (Leagnavar et al., 2015).

The selected research university is a public university in Khon Kaen province, Thailand. Since it is an

established university, the human resource department has a performance assessment system that consists of two

main components: 70 percent of the performance assessment system is used for measuring university lecturers’

work achievement, while the other 30 percent is used for measuring university lecturers’ behavioral performance

(Khon Kaen University, 2015). The core competencies have been identified in accordance with the guidelines

provided by the Civil Service Commission and have been used by the research university since 2011 (Office of

the Higher Education Commission, 2018). Five core competencies are assessed in the performance assessment

system, namely (i) Service Mind, (ii) accumulation of their careers (Expertise), (iii) focus on achievement

(Achievement Motivation), (iv) Teamwork, and (v) adherence to integrity and ethics (Integrity). As a result, the

main aim of this research is to create core competencies and workload-based key outcome indicators for

performance assessment of university lecturers in this public university using functional analysis. This is

followed by examining the quality of the created core competencies and workload-based key outcome indicators

for assessing the university lecturers’ work performance.

2. Method

2.1 Research Design

The researchers chose the documentary research design during the first phase so that they could use the official

documents as sources of material (Ahmed, 2010) to identify core competency expectations from three different

clusters of educational programs. The documentary research design was deemed suitable because it could be

used to assess a set of documents for historical and social value to create a larger narrative through the

investigation of multiple documents surrounding the university lecturers’ work performance. Using this type of

material in the research entails that the documents are recorded as secondary data sources because they contain

material “not specifically gathered for the research question at hand” (Steward, 1984, p. 11).

The expert reviews research design was used in the second phase as a usability-inspection method. As a result,

the five experts examined the developed innovative prototype of university lecturers’ core competencies and

workload-based key outcome indicators with the goal of identifying usability problems and strengths (Harley,

2018). The researchers emphasized the experts’ past experience and knowledge of usability principles. Moreover,

focus group interviews were conducted for four groups of real users to review a set of specifications or more

abstract versions of the users might interface. The focus group interviews were performed via planned discussion

with a small group of real users to obtain their considerations and ideas on the quality of the developed

innovative prototype of university lecturers’ core competencies and workload-based key outcome indicators. The

focus group interviews were practicable for illuminating the variation of viewpoints held by members of the four

groups of real users. Moreover, these focus group interviews were feasible for methodological triangulation with

the five experts’ evaluation.

2.2 Research Procedure and Research Participants

The research involved a preliminary study prior to formulation of a standards-setting appraisal model utilizing a

design research method (Reeves, 2006; Vongvanich, 2020). The preliminary study, composed of two phases,

was employed to determine the core competencies and workload-based key outcome indicators for assessing the

university lecturers’ work performance. In the first phase, researchers conducted documentary research to

investigate the roles, duties, workloads, and working conditions of university lecturers from three different

clusters of educational programs, namely science and technology, health science, and humanities and social

sciences, of a public university in Thailand.

The obtained results from the first phase were used to design and develop an innovative prototype of university

lecturers’ core competencies in the second phase. There were two groups of participants involved in the second

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

84

phase to validate the quality audit performance of the innovative prototype, to examine whether the created core

competencies matched the workload-based key outcome indicators. The first group comprised five experts,

namely three experts from the areas of teaching, research, and academic services in higher education, one expert

specializing in educational measurement and evaluation, and one who is a key individual involved in assessing

university lecturers’ work performance. These five experts were required to rate the innovative prototype in

terms of content validity.

The second group consisted of four focus groups as users of the innovative prototype. The researchers employed

a purposive sampling technique to select the four focus groups. The first focus group consisted of three

informants who are the faculty’s performance appraisal practitioners. The second focus group consisted of nine

university lecturers, three from each respective cluster, namely science and technology, health science, and

humanities and social sciences. The third focus group was the dean or associate dean from each cluster, totaling

three informants. The final focus group included the rector and vice-rector of the human resource division, a total

of two informants. A total of 17 informants participated in user groups for four cycles of the interview, using the

user experience research method.

2.3 Data Analysis

Sources of data from the documentary research and focus group interviews were analyzed using content analysis.

Researchers coded or broke down the text into manageable code categories for analysis. Once the text was coded

into categories, the codes could then be further categorized into themes to summarize data even further. The

documentary data were analyzed using conceptual content analysis, whereby the concept of university lecturers’

core competencies was chosen for examination of the occurrence of selected terms in the data. Terms can be

indicated in the documents implicitly or explicitly. The researchers needed to decide the level of implication and

base judgments on subjectivity for reliability and validity issues for implicit terms.

Content analysis was used to analyze the focus group interview data. The researchers determined the presence of

certain words, themes, and concepts within the given qualitative data. This helped the researchers to quantify and

analyze the presence, meanings, and relationships of such words, themes, and concepts. They then could make

inferences about the messages within the texts of the four groups of real users.

Functional analysis was employed to validate the identified core competencies by the five experts. First, the five

experts selected the main functions and objectives of work according to both the workload and positioning

standards. They began by overviewing, drawing conclusions, and summarizing the core competencies along with

their operational roles. This was followed by breaking down each core competency into its indicators and

elements. All identified core competencies together with their workload-based key outcome indicators were

examined to formulate an innovative prototype, the so-called core competencies measurement model.

The quality audit of the core competencies measurement model was validated using the item content validity

index (I-CVI). A good I-CVI should be 0.78 or higher. The I-CVI was calculated using the formula below (Polit,

Beck, & Hungler, 2006):

I-CVI = Nc / N (1)

Nc identifies a number of experts assessing items at a consistent level

N identifies the total number of experts

I-CVI identifies content validity index for each item

Calculation of item—I-CVI, let experts consider the conformity assessment measure into four levels:

1 means not relevant

2 means partially consistent

3 means quite relevant

4 means very consistent

Moreover, researchers found the scale level content validity index (S-CVI), calculated based on the definition of

CVI, for example, the proportion of items that all experts agreed on regarding whether the item was highly

relevant or relevant to measure:

S-CVI = I-CVI / UA (2)

I-CVI represents item content

UA represents the total number of courses

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

85

S-CVI represents scale level content validity index

3. Results

The results of this research are presented according to the research aim stated previously. The preliminary results

comprise the workload-based key outcome indicators and elements based on the conceptualization of university

lecturers’ core competencies. These results are followed by examination of the quality of the identified core

competencies and their workload-based key outcome indicators, as well as related elements, to assess university

lecturers’ work performance.

3.1 Results of Documentary Analysis

The first phase of the documentary research results provides a list of core competencies that were hypothesized

as the measurement for the work performance of university lecturers. The results reveal that university lecturers’

core competencies comprise four categories, namely teaching, research, academic service, and preserving arts

and culture. The comparative results of the three different clusters of educational programs, namely science and

technology, health science, and humanities and social sciences, indicate that there are differences in core

competencies, except for preserving arts and culture.

On the one hand, the teaching competency of university lecturers from the cluster of science and technology is

focused on improving teaching documents. On the other hand, the teaching competency of university lecturers

from the health science cluster emphasizes using teaching material with advanced technology to interact with

their students. Moreover, the university lecturers also practice specific professional practices in their teaching.

However, the teaching proficiency of university lecturers from the humanities and social sciences cluster reveals

that they are more concerned about supervision of student performance and consultation of students’ classroom

research.

The majority of university lecturers from the science and technology cluster possess research skills as they are

research project leaders. Moreover, they have published their research results in international database journals

with the impact factor, which indexed at Quartile 1 to 2, and have been first authors or corresponding authors.

The documentary results reveal that university lecturers from the health science cluster also possess research

competency and publish their research results in international journals with the impact factor. Moreover, they

utilize these research results to benefit communities and society as well. However, the results reveal that the

research competency of university lecturers from the humanities and social sciences cluster is lacking compared

to the other two clusters because these lecturers only publish in national journals or certain international journals

recognized within their specific field of study.

The results reveal that the three clusters are performing in academic service competency differently. For example,

the majority of university lecturers from the science and technology cluster are receiving scholarship from either

external or international agencies to support them to become project leaders in providing academic services.

Meanwhile, university lecturers from the health science cluster are mainly providing academic services that have

a high impact on communities and society. Finally, university lecturers from the humanities and social sciences

cluster boast educational innovation as their prior academic service to society.

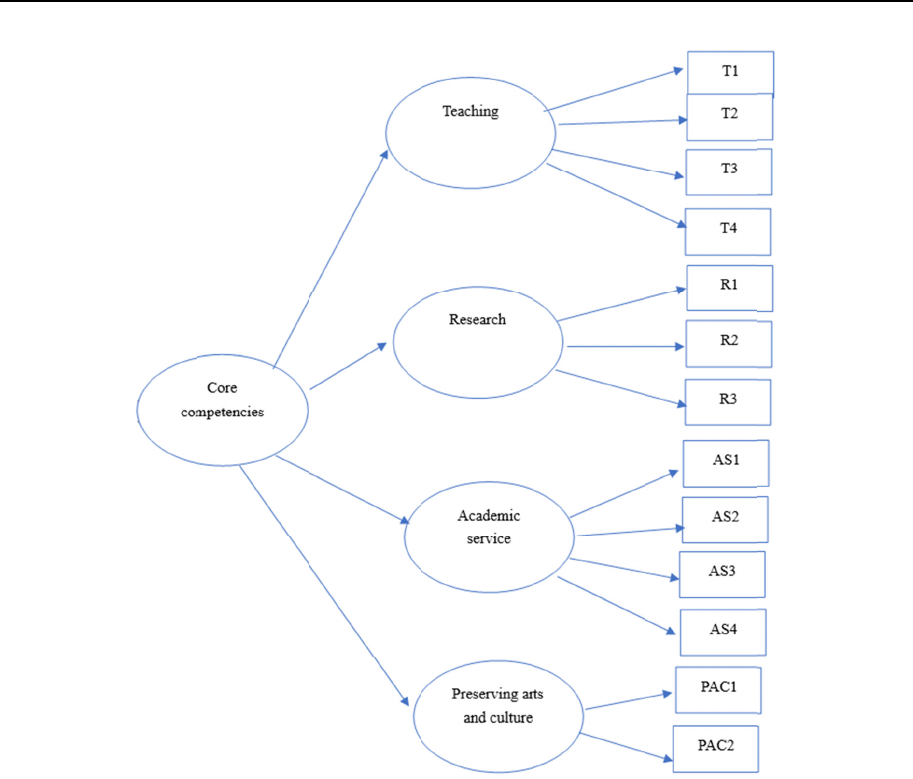

3.2 University Lecturers’ Core Competencies and Their Key Outcome Indicators

The researchers utilized Wyborn et al.’s (2018) suggestions to synthesize the documents related to core

competencies of university lecturers to create an innovative prototype. This was followed by using the user

experience research method for quality audit performance of the innovative prototype of university lecturers’

core competencies. Finally, researchers employed functional analysis to determine the workload-based key

outcome indicators and elements derived from the identified core competencies. The preliminary results reveal

that there are four core competencies of university lecturers, namely teaching, research, academic service, and

preserving arts and culture. Furthermore, there are 13 workload-based key outcome indicators and 27 elements

that resulted from the four core competencies with regard to the specific research university in the Thai context.

Table 1 details the core competencies, their workload-based key outcome indicators, and their elements, while

Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of core performance mode using the functional analysis method.

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

86

Table 1. Identification of core competencies and their workload-based key outcome indicators

Core Competencies Key Outcome Indicators Elements

Teaching Knowledge development (T1) Attending training for new knowledge in their field (T1.1)

Attending academic meetings in their scientific field (T1.2)

Participating in academic presentations in their field (T1.3)

Knowledge transfer (T2) Systematic teaching planning (T2.1)

Teaching media (T2.2)

Students’ satisfaction (T2.3)

Use of digital technology in

teaching (T3)

Using digital technology in online teaching (T3.1)

Digital interaction media (T3.2)

Online lessons (T3.3)

Compiling essence of subject

matter (T4)

Summarizing the contents of subject matter (T4.1)

Preparing teaching documents according to the course contents (T4.2)

Writing textbooks/books of subject matter (T4.3)

Research Research output (R1) Number of research results that have been conducted (R1.1)

Number of publications in the national or international database (R1.2)

Research awards (R1.3)

International research

recognitions (R2)

Number of publications in the international database (R2.1)

Number of research results with researchers from foreign institutions (R2.2)

Number of research papers presented at the international level (R2.3)

Research funding acquisition

(R3)

Receiving research funding from internal funding sources (R3.1)

Receiving research funding from external funding sources in Thailand

(R3.2)

Receiving research funding from external funding sources in foreign

institutions (R3.3)

Academic service Integration with teaching (AS1) Designing academic services for teaching use (AS1.1)

Integration with research (AS2) Designing academic services for research use (AS2.1)

High impact academic services

(AS3)

Providing academic services that have high impact on the social community

(AS3.1)

Matching the expertise (AS4) Providing academic services that match their expertise (AS4.1)

Preserving arts and

culture

Activity participation (PAC1) Participating in arts and culture preservation activities (PAC1.1)

Creation of activities (PAC2) Creation of activities to preserve arts and culture (PAC2.1)

jel.ccsenet.

o

F

3.3 Qualit

y

3.3.1 Qua

l

A total o

f

competen

c

outcome

i

competen

c

using fun

c

higher, as

competen

c

with the u

n

that the c

o

workload,

o

rg

F

igure 1. Dist

r

y

Audit Perfo

r

l

ity Audit Per

f

f

five experts

c

ies and their

w

i

ndicators de

r

c

ies (S-CVI),

w

c

tional analys

i

displayed in

T

c

ies at Level

4

n

iversity lectu

o

re competen

c

such as the u

s

r

ibution of cor

r

mance Result

s

f

ormance Res

u

participated

i

w

orkloa

d

-

b

as

e

r

ived from e

a

w

ere consiste

n

i

s from rating

T

able 2. Table

4

, indicating t

h

rers’ workloa

d

c

ies were con

s

s

e of digital te

c

Journal of E

d

e performanc

e

s

of Core Co

mp

u

lts Rated by

F

in the secon

d

e

d key outco

m

a

ch core com

p

n

t with the wo

r

scales of the

2 demonstrat

e

h

at they foun

d

d

. However, t

h

s

idered relativ

c

hnology in te

a

d

ucation and L

e

87

e

mode and w

o

mp

etencies and

F

ive Experts

d

phase of th

i

m

e indicators.

T

p

etency, eith

e

r

kload of uni

v

e

five experts,

e

s that most o

d

the identifie

d

h

ere are some

c

ely consistent

a

ching (T3) a

n

e

arning

o

rkloa

d

-

b

ased

k

Workload-Ba

s

i

s research fo

r

T

hey were req

u

e

r in the co

m

v

ersity lecturer

indicate that

f the experts

r

d

core compe

t

c

ore compete

n

with or quit

e

n

d high impac

t

k

ey outcome

i

s

ed Key Outc

o

r

quality aud

i

u

ired to exami

m

petency list

(

s or not. The

q

the conformi

t

r

ated the perf

o

t

encies were

a

n

cies rated at

L

e

relevant to

u

t

academic ser

v

Vol. 10, No. 6;

i

ndicators

o

me Indicator

s

i

t of the four

ne whether th

e

(

I-CVI) or o

v

q

uantitative re

t

y index is 0.

7

o

rmance of th

e

a

ccurate and i

n

L

evel 3. This

m

u

niversity lect

u

v

ices (AS3).

2021

s

core

e

key

v

erall

s

ults,

7

8 or

core

n

line

m

eans

u

rers’

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

88

Table 2. Results of content validity index

Core competencies Expert No. of an expert

agreed

I-CVI

(Item)

Result

1 2 3 4 5

T1 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

T2 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

T3 4 4 3 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

T4 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

R1 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

R2 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

R3 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

AS1 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

AS2 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

AS3 4 4 3 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

AS4 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

PAC1 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

PAC2 4 4 4 4 4 5 1.00 Relevant

3.3.2 Quality Audit Performance Results Through User Experience Method

The researchers employed the user experience method to conduct four cycles of focus group interviews with four

key groups of informants who were involved directly in assessing university lecturers’ work performance. These

four key groups consisted of practitioners, university lecturers, the dean or associate dean, and the rector or

vice-rector of the human resource division of the research university. These persons are currently using the

guidelines provided by the Office of the Civil Service Commission (Office of the Higher Education Commission,

2018). The researchers intended to obtain wide-ranging views from users’ perspectives to determine the quality

of the performance results of core competencies and workload-based key outcome indicators in terms of their

appropriateness and consistency.

The researchers practiced triangulation of interview data from four perspectives to enhance the validity of the

collected data (Gay, Mills, & Airasian, 2011). According to Gay et al., the compelling viewpoints of qualitative

research remain in the triangulation of numerous methods, data collection, and data sources to obtain a more

detailed illustration of the idea under research and also to enable researchers to cross-check information. Content

analysis was utilized to analyze the obtained interview data by identifying, analyzing, and reporting the themes

within the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The following verbatim interview records from the group of practitioners are responsible for performance

appraisal commented about the gap of the current performance appraisal to measure accurately between

university lecturers’ core competencies and their actual workload. Moreover, they suggested that the

standard-setting appraisal system should be a reference only, the dean of each faculty has to make necessary

adjustments based on their context.

The following verbatim interview records from the group of practitioners are responsible for performance

appraisal, and mention the failure of the current performance appraisal to measure accurately the difference

between university lecturers’ core competencies and their actual workload. Moreover, they suggested that the

standard-setting appraisal system should be a reference only and that the dean of each faculty should make

necessary adjustments based on their context:

“The indicators for assessing performance are quite abstract. The empirical evidence used to support the

assessment was not clearly stated. As a result, the assessors used their discretion to assess, and allowed

their subordinates (university lecturers) to have full scores for all categories, including core competencies

and behavioral outcomes.”

“There should be a standard-setting performance appraisal system that is the central standard of the

university, and each faculty can adjust using additional and appropriate details depending on the context of

the faculty.”

The second group comprised the university lecturers who revealed that the empirical evidence to support the

core competencies was not defined clearly as a standard. They complained that the level attained in the

performance appraisal should indicate clearly how university lecturers can improve in future to obtain a higher

level of performance assessment results. The verbatim interview records are presented according to the related

issue as follows:

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

89

“Empirical evidence requires such as performance reports to assess core competencies is not clearly

defined as a standard.”

“The level of performance assessment results in each assessment cycle did not show clearly what kinds of

improvements we had to make for the next round to have a higher level of performance assessment

results.”

The third focus group comprised of deans or associate deans who have the role of assessors. They commented on

the core competencies used to assess the university lecturers’ work performance, stating that the broad

characteristics, such as good service (Service Mind), do not make clear how they can be measured based on

lecturers’ workload. They suggested that the core competencies in the current work performance appraisal

should be used as the central standard of the university and established based on the practical workload.

Moreover, faculties should be allowed to further adjust in accordance with their context. The following verbatim

interview records reflect the deans’ or associate deans’ views regarding the current work performance

assessment system:

“Core competencies that assess the performance of university lecturers in the present have broad

characteristics such as good service (Service Mind), etc. It does not specify how it is measured by their

workload.”

“The core competencies used in the university lecturers’ work performance assessment should be

established based on the practical workload. It should be the central standard of the university and the

faculties can further adjust according to their context.”

The final focus group consisted of the rector and vice-rector of the human resource division. Their interview

results indicated that the current performance appraisal should reflect the areas that need further development.

For example, if a university lecturer has achieved the highest rating of expectation, the assessment criteria should

be adjusted accordingly. Furthermore, they recommended that all parties should be encouraged to be involved

because mutual recognition based on actual practices, clear indicators, and criteria is important for every

individual to accept and understand. Finally, they agreed that performance assessment results must reflect the

strengths and their indicators that need to be developed individually. This is expected to substantially benefit

future personnel management of the organization. These themes are derived from the following verbatim

interview records:

“Performance assessment itself should be an assessment to reflect the areas that need further development.

If the university lecturers being assessed have achieved the highest rating, expectations and assessment

criteria should be adjusted accordingly.”

“Determining the core competencies used in the assessment system should emphasize the participation

from all parties involved and mutual recognition based on actual practices. There are clear indicators and

criteria that can make everyone accept and understand.”

“Performance assessment results must be able to reflect strengths and points that need to be developed

individually. This is for the benefit of further use in personnel management of the organization.”

4. Discussion

This is a preliminary study mainly aimed at creating and validating the university lecturers’ core competencies

and workload-based key outcome indicators before researchers develop a standards-setting appraisal

measurement model for a public university in Thailand. Therefore, rating the performance assessment tool is a

fundamental technique to ensure that the job analysis can support consistency for university lecturers’ work

performance. For this work, the major concern was to offer reliable and valid means of collecting data and to

focus on the critical core competencies to create an innovative prototype. The results of this preliminary study

have successfully approved the quality of this innovative prototype with validation from five experts and 17

users.

It can be concluded that such a robust appraisal measurement model can provide university lecturers with

meaningful and quality feedback and generate consistent use of performance appraisal data for administrative

decisions such as merit pay, promotion, and tenure (Akbar Ali & Si, 2015; Lohman, 2021). Since past

researchers (Cordoso, Tavares, & Sin, 2015; Herdlein, Kukemelk, & Türk, 2008) have raised questions about the

quality of performance appraisal practices and noted poor alignment with institutional missions, the researchers

would like to recommend the ideas of Allen et al. (2012), Hocking et al. (2008), and Leagnavar et al. (2015) to

confirm the key outcome indicators so that they are specific, measurable, achievable and attributable, relevant

and realistic, and time-bound, to solve the problems of poor alignment. Finally, a key suggestion for improving

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

90

university lecturers’ work performance is to enhance their core competencies through professional training so

that they can conduct better scientific research and transfer the scientific results to their students (Blašková et al.,

2014)

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of service and facilities of the Faculty of Education, Khon Kaen

University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand. The contents of this manuscript are derived from the first author’s

doctoral dissertation thus fulfilling the Ph.D. requirement of Khon Kaen University.

References

Ahmed, J. U. (2010). Documentary research method: New dimenisions. Indus Journal of Management & Social

Sciences, 4(1), 1−14.

Akbar Ali, H., & Si, M. (2015). Performance lecturer’s competence as the quality assurance. The International

Journal of Social Sciences, 30(1), 30−45.

Allen, W., Fenemor, A., & Wood, D. (2012). Effective indicators for freshwater management: Attributes and

frameworks for development. Landcare Research NZ Ltd, Christchurch, New Zealand. Retrieved from

http://www.learningforsustainability.net/pubs/developing-effective_indicators.pdf

Blašková, M., Blaško, R., Jankalová, M., & Jankal, R. (2014). Key personality competencies of university

teacher: Comparison of requirements defined by teachers and/versus defined by students. Procedia

−

Social

and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 466−475.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.731

Blašková, M., Blaško, R., & Kucharþíková, A. (2014). Competences and competence model of university

teachers. Procedia

−

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 457−467.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.407

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Psychology, 3, 77−101.

https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cardoso, S., Tavares, O., & Sin, C. (2015). The quality of teaching staff: Higher education institutions’

compliance with the European standards and guidelines for quality assurance—The case of Portugal.

Educational Assessment Evaluation and Accountability, 27(3), 205−222.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-015-9211-z

Gay, L. R., Mills, G. E., & Airasian, P. W. (2011). Educational Research. New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Harley, A. (2018). UX expert reviews. Nielson Norman Group: World leaders in research-based user experience.

Retrieved from UX Expert Reviews (nngroup.com).

Herdlein, R., Kukemelk, H., & Türk, K. (2008). A survey of academic offcers regarding performance appraisal

in Estonian and American universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 30(4),

387−399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800802383067

Hockings, M., Jacobson, C., & Carter, R. W. (2008). Process guidelines for indicator selection in protected area

management effectiveness evaluation: Building capacity for adaptive management of protected areas.

Report to the Natural Heritage Trust. Brisbane, Australia: The University of Queensland.

Khon Kaen University. (2015). Criteria and methods for evaluating the performance of personnel. Khon Kaen,

Thailand: Khon Kaen University printing house.

Legnavar, P., Bours, D., & McGinn, C. (2015). Good practice study on principles for indicator development,

selection, and use in climate change adaptation monitoring and evaluation. Climate-eval community of

practice, Washington DC. Retrieved from

https://www.climate-eval.org/study/good-practice-study-principles-indicator-development-selection-and-us

e-climate-change

Office of the Higher Education Commission. (2018). Guidelines for enhancing the quality of teaching and

learning management of instructors in higher education institutions. Bangkok, Thailand: Prints.

Polit, D., Beck, F. C. T., & Hungler, B. P. (2006). Essentials of nursing research: Methods, appraisal, and

utilization. New York, NY: Lippincott.

Reeves, T. C. (2006). Design research from a technology perspective. In J. V. D. Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S.

McKenney & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational Design Research (pp. 52−66). New York, NY: Routledge.

Steward, D. W. (1984). Secondary research: Information sources and methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

jel.ccsenet.org Journal of Education and Learning Vol. 10, No. 6; 2021

91

Vongvanich, S. (2020). Design research in education. Bangkok, Thailand: Chulalongkorn University Printing

House.

Wyborn, C., Louder, E., Harrison, J., Montambault, J., Montana, J., Ryan, M., … Hutton, J. (2018).

Understanding the impacts of research synthesis. Environmental Science and Policy, 86, 72−84.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.04.013

Copyrights

Copyright for this article is retained by the author, with first publication rights granted to the journal.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).